Ur was a city near Sumer, southern Mesopotamia, in what is modern-day Iraq. According to biblical tradition, the city is named after the man who founded the first settlement there, Ur, though this has been disputed.

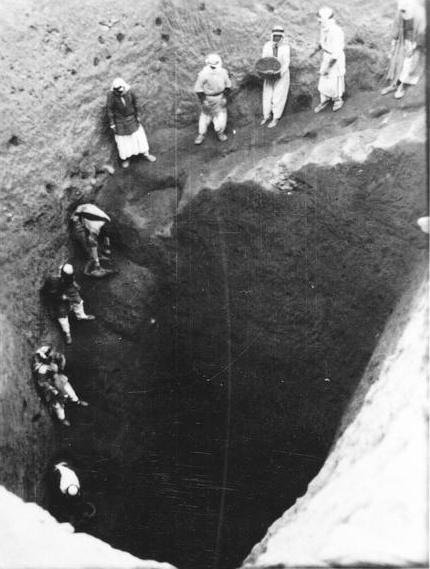

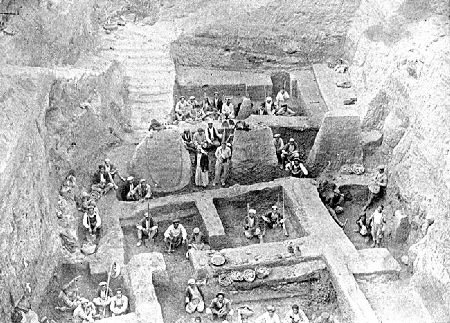

The Great Death Pit at the ancient city of Ur, in modern-day Iraq, contains the remains of 68 women and six men, many of which appear to have been sacrificed. During Sir Charles Leonard Woolley’s excavation of Ur from 1922 to 1934, they gave any burial without a tomb chamber the name ‘death pit’ (known also as ‘grave pits’).

Arguably the most impressive death pit excavated by Woolley and his team was PG 1237, which Woolley dubbed as ‘The Great Death Pit’, because of the number of bodies that were found in it. These bodies were arranged neatly in rows and were richly dressed. It is commonly believed that these individuals were sacrificial victims who accompanied their master/mistress in the afterlife.

It is unclear, however, if they had done so voluntarily. During Woolley’s archaeological excavations at Ur, six burials were assigned as ‘death pits’. Generally, these were tombs and sunken courtyards connected to the surface by a shaft. These ‘death pits’ were thought to have been built around or adjacent to the tomb of a primary individual.

This hypothesis, however, has been challenged in recent times. In any case, the ‘death pits’ discovered by Woolley and they filled his team with the remains of retainers belonging to an important individual. The most impressive of Woolley’s ‘death pits’ is PG 1237, which was named by Woolley as the ‘Great Death Pit’.

In this ‘death pit’, Woolley and his team identified 74 individuals, six of whom were male and the rest female. The bodies of the six men were found near the entrance of the ‘death pit’ and were equipped with a helmet and weapons. In the Old Babylonian Period (c. 2000-1600 BCE) Ur remained a city of importance and was considered a center of learning and culture.

According to the historian Gwendolyn Leick, “The `heirs’ of Ur, the kings of Isin and Larsa, were keen to show their respect to the gods of Ur by repairing the devastated temples” (180) and the Kassite kings, who later conquered the region, did the same as would the Assyrian rulers who followed them.

The ruins of Ur today are a significant archaeological site that continues to yield important artifacts when the troubles of the region allow. The great Ziggurat of Ur rises from the plains above the mud-brick ruins of the once-great city and, as Bertman suggests, in walking among them one relives the past when Ur was a center of commerce and trade, protected by the gods, and flourishing amidst fertile fields.