Afghans have plenty of serious issues to contend with, but a surprising number of them are concerned with a number, 39. Many cultures consider certain numbers to signify luck or disaster. In Afghanistan, 39 is taboo.

It’s hard to find a credible story to explain what exactly it means, but everyone knows it’s bad. Many Afgha

ns say that the number 39 translates into morda-gow, which literally means “dead cow” but is also a well-known slang term for a procurer of prostitutes — a pimp.

In Afghanistan, being called a pimp is offensive, and calling someone a pimp could carry deadly consequences. Similarly, being associated with the number 39 — whether it’s on a vehicle license plate, an apartment number, or a post office box — is considered a great shame. And some people will go to great lengths to avoid it.

“I recently bought a new Toyota car. Every time I drive to my new home in Kabul, kids call me ’39,’ ” says Arif Zahir, 30-year-old Kabul resident. “It is because of my license plate, which has the number 39,” Zahir says that his car cost him $16,000, but the 39 plates have reduced its value by half.

Some people say a famous ne’er-do-well in the western Afghan province of Herat had 39 on his car, and now anyone with that number faces everything from snickering to outright disdain.

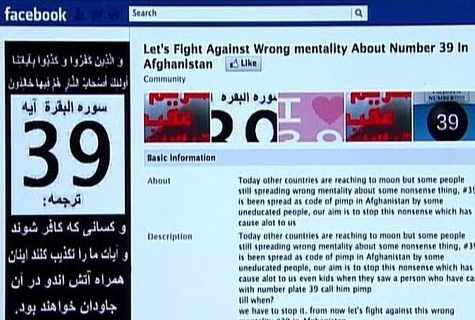

Others say it’s been a taboo for years, and the arrival of mobile phones and increasing access to the Internet has spread it to other cities in Afghanistan.

“In Herat, the number 39 has been a taboo for year

s. People have changed their phone numbers, addresses and now it has hit car owners,” says resident Mohammad Tamim Abdullah.

“In Herat, when the vehicle registration number reached 39,000, people kept waiting for months for it to pass this number before they would apply for new license plates.” Traffic authorities in Kabul blame car dealerships for starting the craze.

“Car dealerships and those who work for the mafia started the rumors about 39 so they could buy cars with 39 plates cheaper and sell them back for higher prices after changing the plates,” says Abdul Qader

Samoonwal, an official at Kabul’s Traffic and License Registration department.

Abdul Matin, who owns a car dealership in Kabul, rejects such allegations. “We don’t know how the taboo about the number 39 started, but it’s not the car dealerships,” he says.

The head of Kabul’s motor and traffic department recently organized roundtable discussions to dispel any taboo with the number 39. He went on Afghanistan’s TV channels with prominent imams and a controversial but well-known Afghan mathematician, Sediq Afghan.

“We warned people that any word, offensive or otherwise, could come up if we use numerology,” Afghan said.

The imams also warned that the Quran, the Muslim holy book, contains verses that are numbered at 39. Associating the number with pimps “is a sin because 57 Suras from our Quran contain the number 39,” Af

ghan said.

Yet it does not seem to have allayed the fears of many Afghans. In fact, some Kabul residents say that a warlord running for Parliament in last year’s election attacked two people after he was called 39. Some say he had 39 in his ballot number.

Some drivers have come up with creative ways to hide 39 in their license plates. They punch holes in the middle of the number “3” to make it look like “8.” Others cover their license plates with a blue or gray sheet of plastic. Some have even painted over the number in white.

Waseh, an Afghan driver with an international nongovernmental organization in Kabul, says he was recently shocked to discover that one of the cars assigned to him has a license plate number that begins with 39.

“I have no choice but to drive this car since I earn my living working here,” Waseh says. “But I have to cover the 39 plates with a blue sheet. I do this to protect the dignity of this organization and also of myself.”

Waseh is also facing another problem: He is 39 years old. When as

ked how he copes, he says he tells people that he is yak kam chehl — one year till 40.

As Afghanistan welcomed the New Year and a new decade on March 21, some were not sure what to make of the year’s numerical composition: It’s 1390 in Afghanistan, and that means Afghans have to either cope with it or forget the fact that they will be stuck with a 39 in their calendar for a whole decade.